Catherine “Erin” Salthouse is a Museology M.A. Candidate from the University of Washington. She has put on programs at the Museum of Flight, the Pacific Science Center, and the Cartoon Art Museum and has over 3 years experience creating youth programming in other cultural institutions.

Autism in Museums is adapted for the Midwest from a post for the Western Museums Association Feb 21, 2017.

The upcoming AMM conference theme of Strong Roots and Thriving Communities brings to mind many perspectives and audiences. I am writing today to share my experience and understanding of one in particular: individuals with ASD.

I remember sitting in a middle school library, answering questions about how I would react to student misbehavior. I was terrified. I was about to work with kids with autism for the first time and I had no idea what to do. I accepted the job because I liked teaching teens, I was broke, and nothing could be much worse than night shifts at a postal distribution center. I’m being completely honest when I say that working with teens with autism changed my life.

Dr. Stephen Shore is often quoted for saying, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” For every student, I had to adjust and customize how I facilitated their learning. It was exhausting, but also rewarding. I arranged a field trip to the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, and I recall one teacher’s shock when I let the students wander the galleries without a worksheet or lecture. But the students had a great time. There were no crowds, loud noises or bright lights, and the students had a quiet area to retreat to if necessary. It was free-choice informal learning, just what many museums are designed for. Working with those students made me passionate about welcoming people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) into museum spaces and is the reason I went to grad school.

Many museums offer early open events to families with children with autism much like the field trip I described: a regular, often monthly, subdued version of the museum at low or no cost. Lisa Jo Rudy sees these kinds of events as first steps for many museums interested in inclusive initiatives. She has written a passionate book and maintains a blog on this topic. After establishing successful early opens, many museums move beyond autism exclusive events toward more integrated programs. The Transit Museum in Brooklyn and the Intrepid, Sea, Air and Space Museum have some excellent programs.

During an internship at the Pacific Science Center I was able to talk with some staff about their experiences during the early open event. In addition to opening the doors early and turning down the lights, science education staff at the Science Center are present at core stations like the tide pool, the planetarium, and the butterfly house to facilitate. They also run a low-key live science show featuring a snake. Everyone I spoke to was glowingly positive about the early open event. Some had attended an accessibility training offered by Partners for Youth with Disability, which made them more confident in their ability to communicate, not just with visitors with autism, but with all guests. Additionally, some felt that because there were fewer people in the museum, they could have longer, more impactful interactions with visitors.

The autism rate is now 1 in 68 children, so this population requires more and more museums to be versed in accommodations and facilitations. There are a few guides, like this one from the Boston Children’s Museum designed to help museums create great programs for visitors with autism, but I have not been able to find anything that deals with the logistical side of things. So that is what I’ve focused my thesis research on – understanding the resources and planning necessary to put on an early open event. I’m still in that process, but I can tell you some things I have discovered.

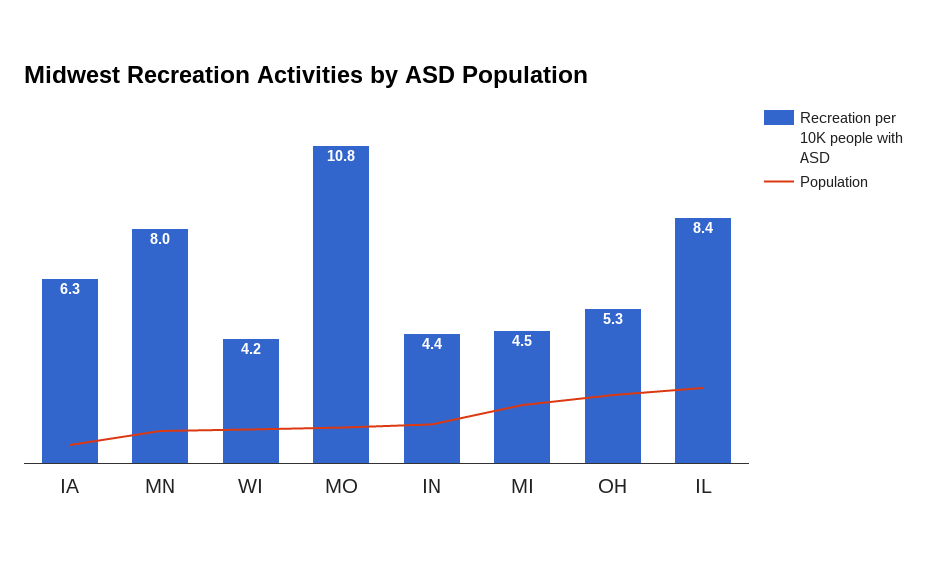

I looked at the number of listings on Autism Speaks for local support groups and community or recreational activities (which may include museum programs) by state on February 5, 2017. Then I compared this to each state’s population. Here is what the information on Midwestern states reveal.

*per 10K people with ASD, based on CDC estimate of 1 person with ASD per 68 people.

You can see from the chart that there are four to ten recreational activities per 10,000 people with ASD in any given state. I think museums can increase that ratio. On the East coast, it is consistently higher: Delaware (10.7), New York (11.1), Vermont (12), Connecticut (13.3), and New Jersey (15.1) all score over ten. Museum programs and events can increase the ratio of recreational options for people with ASD and create more opportunities for this growing population. There are already some good examples of museum based autism programs and events under way in your region: The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art has partnered with Autism Society in the Heartland and Joshua Center to create a great art workshop, The Children’s Museum of Cleveland partnered with the Cleveland State University’s Physical Therapy Department, and The Grand Rapids Children’s Museum recently received the Autism Alliance of Michigan’s Seal of Approval.

The American Association of Museums claims “Diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion in all aspects of museum structure and programming are vital to the future viability, relevance, and sustainability of museums.” This is especially important for growing populations, like people with ASD. Museum-based autism programs benefit more than just the children with ASD. Lisa Jo Rudy (2010) claims that visiting museums and other cultural offerings are impactful for both children with ASD and for their parents or caregivers. Smith & Anderson (2014) found that parents or caregivers of children with ASD experience more strain than parents of children with other kinds of disability. More specifically, Kulik & Fletcher (2016) found that parents of children with ASD reported experiencing three times as many negative emotions associated with museum activities as parents with typically developing children. Getting parents (and thus children with ASD) into your museum would be most successful with an active invitation through targeted events and programs.

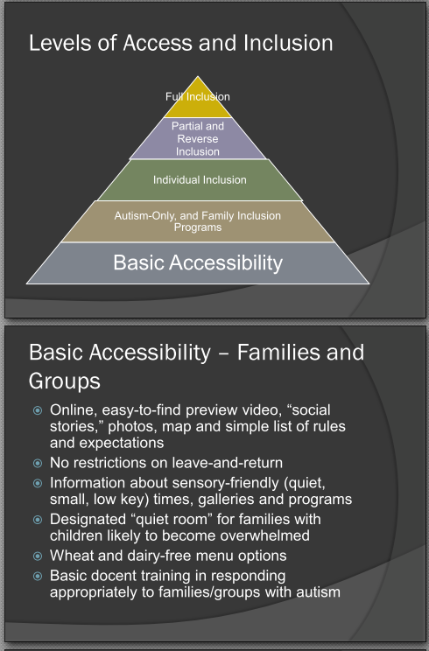

Now you might say, how is welcoming families with children with ASD into my museum beneficial to the wider community? The few hours they spend at the museum is secluded, exclusive, and seems very different from the “average” visitor. But the growth of ASD in our wider population makes this something impossible to ignore for long. I believe an early or late open event at a museum is just the first step, as you can see from the pyramid below. An early open helps people with autism become familiar and comfortable with the museum so that they may be able to subsequently try more integrated and less supportive atmospheres. In my research, I have found the accessibility training that usually accompanies an early open kind of event gives staff confidence and new skills for interacting with all guests, not just those with special needs.

Welcoming families with children with ASD into a museum with an early open does not condemn museum practices to segregation of communities, but rather provides support for a group of visitors who needs it, like ramps, verbal description tours, and reduced admission fees. The social model for disability looks at the barriers society has created, rather than medical differences. Through this model, we can see that for someone with ASD, the overwhelming stimuli of large crowds, bright lights, and loud noises are barriers to accessing the museum content. Luckily, these elements are easy to adapt and modify for few hours, at little cost to the museum and with high impact for the visitor who would otherwise be unable to enjoy the experience.

(Image borrowed from Lisa Jo Rudy: http://www.autisminthemuseum.org/p/blog-page_20.html)

Working with a new audience can be intimidating- I imagine a lot of museum professionals are terrified of not knowing what to do like I was. But it is worth doing. Reach out to a local advocacy group, coordinate with other museum professionals. Some early open events at museums are collaborations with local university programs, so extensive accessibility training for staff may not be required off the bat. Some museums have an autism day once a year or quarterly before committing to a monthly event.

Resources exist to help you get started. Museum Access Consortium (MAC) and the Chicago Cultural Accessibility Consortium (CCAC) offer great online resources. Assuming children with autism are spread evenly through the population, Illinois will have over 180,000 children with autism spectrum disorder. What can your museum do to welcome them?

References:

Kulik, T., & Fletcher, T. (2016). Considering the Museum Experience of Children with Autism. Curator: The Museum Journal, 59(1), 27-38.

Rudy, L. J. (2010). Get out, explore, and have fun! how families of children with autism or asperger syndrome can get the most out of community activities. London: London : Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Smith, L., & Anderson, K. (2014). The Roles and Needs of Families of Adolescents With ASD. Remedial and Special Education, 35(2), 114.